A mountain I love a lot started to come into view about half an hour after I began cycling from Matamata early this morning. I was eager for my first glimpse because Maungatautari symbolises much about the past, present and future of our ecosystems.

The fringe of native forest on its upper slopes and summit is one of the few untouched fragments left in the Waikato. Almost the whole province was cleared of bush to make way for farms, beginning in the 19th century. That has made the Waikato the traditional and wealthy centre of the dairy industry, though in recent decades dairying has grown fast down in the South Island and elsewhere.

But dairy farming has extracted the largest toll on land, water and biodiversity, here and around the country. The other big destroyer of biodiversity are wild mammals such as possums, rats and stoats which we humans have brought to Aotearoa.

Maungatautari is important because it was an early victim of those ecological pressures; and because it is an early example of how to restore and regenerate. Some of it was made a reserve as far back as the early 20th century. But the real restoration began in 2001 with the creation of the Maungatautari Ecological Island Trust. The plan sounded far-fetched at the time: build a 47km predator proof fence to keep the likes of possums which eat the tree leaves and rats that eat birds’ eggs out of 3,400ha of the mountain.

A few years after the fence was finished, Lynn, Celeste and I visited the mountain and even at that early stage we could see the bush regenerating. And the progress has been spectacular since. Native trees and plants are thriving, as are native species of birds, bats, frogs, reptiles, tuatara and giant weta. Today, Maungatautari gives us a partial idea of what the pre-human environment was like in Aotearoa.

As you see in the photo above, the native bush is lush, dark green. It is surviving the latest of our increasingly frequent droughts where as the farmland below is not. However, some farmers are working on better systems. One example is the Williams family who have farmed land between the mountain and Lake Karapiro for four generation. They combine organic farming, wetlands restoration, robotic milking, bee keeping and food crop diversification as some of their key practices. This article describes their journey, and this website their range of activities.

The Tour route took me this morning to the foot of the mountain at Lake Karapiro, which was created by one of a series of hydro-electric dams built on the Waikato river before and after the Second World War. I spent much of the rest of the day following the river upstream on the bike trail.

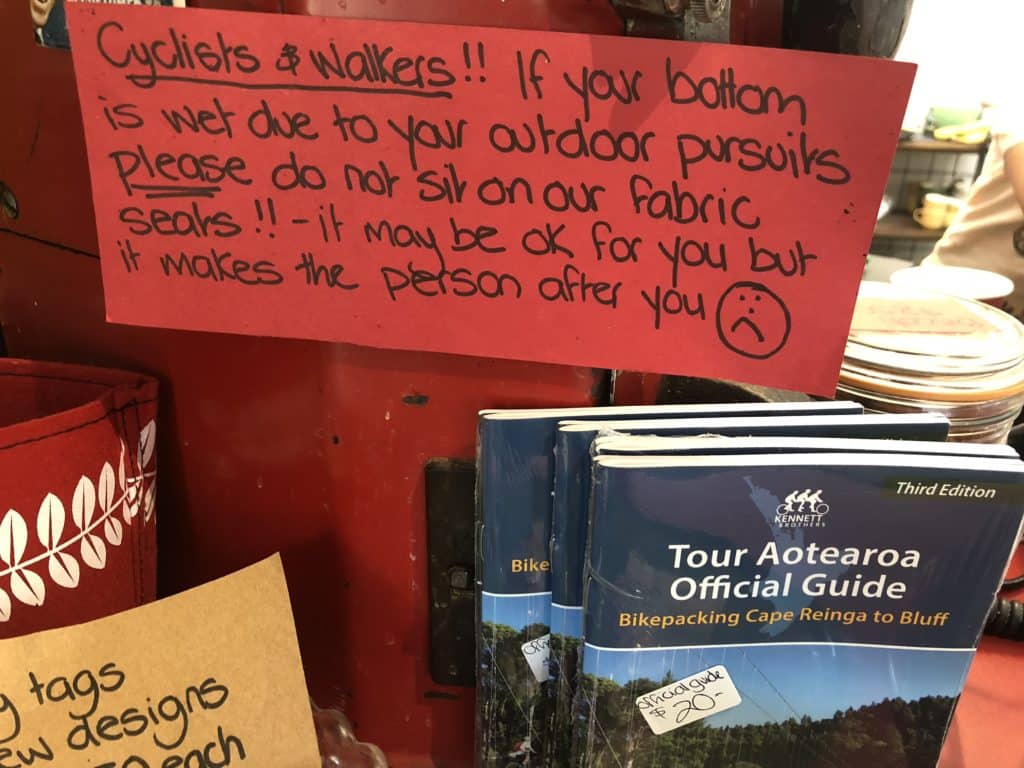

I stopped for lunch at the famous Rhubarb cafe by the Awapuni dam.

After lunch, the next stage of the river trail had been closed, so I and other riders took an inland route through remote Waikato hill farming country. It was gorgeous landscape on very quiet back roads, a part of the Waikato that’s probably unfamiliar to many.

Along the way, a thunderstorm long brewing finally delivered a short dump of hailstones and a mass of suddenly cold air. I took shelter under two enormous trees at the gate of a farm, as did Jayne from England. She is on a very special bike. The frame is made from bamboo, and she made the bike in a workshop in London, and called it Bamboo Betty, after her dearly departed grandmother. Jayne’s here for three months of travels and adventures.

After another 100km day, tonight I’m in Mangakino, another of the towns down the river created at each dam site for construction workers. I’m in a cabin tonight with three other riders I’ve got to know. Rather than camp, we’re taking a softer option as we prepare for the next three days through very rugged hill country. I hope to get a mobile signal tomorrow night. But If I don’t I’ll be back with you as soon as I can.

0 Comments